How Improv Comedy Can Help When Dealing With Difficult Clients

Hold your ground in a disagreement while not insulting your client’s intelligence. Learn “mental aikido” to mold client expectations without emotionally triggering them.

Most freelance designers and agencies know the “client from hell” archetype. This client has false assumptions about how your work is done, how much it costs, how long it takes, and what the final product will be like. They might micromanage you or your team, change their mind with the wind, and cause all kinds of headaches if you don’t take charge and let them know you’ve got it all under control without their “help.”

The problem is: how do we take control of the situation without embarrassing or angering “the boss”?

An otherwise strong design team leader who doesn’t possess great “people skills” might come down harshly on the overzealous client, triggering emotions and upsetting them. This doesn’t bode well for referrals or future work with this company.

In today’s competitive environment, our responsibility on contracts is to get the job done right while properly managing our clients’ expectations (and emotions) during the process. To boot, we need them to rave about us afterwards on social media! How can we do that when an overbearing client annoys us at every step on the journey?

Perhaps the solution lies in Whose Line is it, Anyway? Since the totally unscripted show came on the air in the late 1980s in Great Britain and later the USA, improv comedy training has become increasingly more prevalent in business leadership training. Here are a few nuggets about client management that you might learn in an applied improvisation class.

What I Like About That Is …

One game you can practice with your whole team – to prepare them for clients making flat-out-wrong statements or asking for things that they don’t actually want – is called “What I Like About That Is …”

This game demonstrates how we can coax the client into opening up and being honest and vulnerable with us, instead of treating us as inferior “hired help” and making demands.

Have one person play the designer and the other play the problematic client.

The client comes in and says something like, “On my meditation and mindfulness website, I want to sell 75% of the homepage space to banner ads for assault rifles because that’s a very profitable industry.”

The designer might want to simply call the client a “contradictory lunatic.”

But in this exercise, the designer must begin all of their responses with “What I like about that is…”

So instead of immediately refuting the ridiculous suggestion or making it wrong, the designer looks for something or anything – no matter how small – that they can compliment in what the client has said. In this case they might respond, “What I like about that is you’re definitely keeping your eye on making a profit with the available space on your site.”

Notice that the designer has “disagreed” with the client in a totally non-confrontational way. By honestly complimenting the desire behind the demand, you are subtly taking control and softening their defenses.

I liken this technique to a “mental aikido.” Aikido is a martial art that uses the opponent’s own energy to eventually subdue them. Instead of meeting blows with blows, aikido meets blows with flexibility. Likewise, responding to the client in a charitable way, you are subtly directing the energy into a place where you can eventually direct it where you’d like it go.

In most client confrontations, what we really need is for our client to open up and be honest with us about what their true concerns are, as opposed to making demands.

So the client continues, “Exactly, we need to make $1000 every time someone clicks on our site.”

The designer knows that $1000 in profit per click is an unreachable amount, but digs into their well of charitable responses and says, “What I like about that is, you’ve got set goals about what financial success means for you.”

So again, instead of telling the client, “That’s impossible, keep dreaming!,” we’ve actually affirmed them for something that truly is good: having goals. We’ve already gone one layer deeper – first the client was talking about types of ads, now they are talking about specific financial goals behind wanting those ads. We’re making progress and moving towards a truthful, vulnerable conversation. The dialogue will soon be in a place where we can take control.

Now the client responds, “Yeah, it’s a been tough year so we have to make up for all the profits we’ve lost in 2020.”

Now, the designer has an opening, because the client, feeling heard, has stopped making insane demands. The client is now being vulnerable by sharing about their lost revenue. The freelancer can see what the client’s true concern is: “We are in the hole financially and we need to dig out of it as quickly as possible.”

The designer can now say, “What I like about that is you really care about making your company profitable in the long term. Have you thought about standing by your own products and using a more traditional landing page for them on the homepage?”

Notice that we give a charitable response to our client, and follow it up with a question as opposed to a more confrontational professional recommendation.

That’s our next skill.

Making Your Partner Look Good

In improv comedy, actors take the stage with no script. Usually given a one-word suggestion from the audience, they must create a funny scene on the spot. As a result of everything being off the top of their heads, the actors constantly make mistakes. To offset this, improvisers abide by a a rule called, “Make Your Partner Look Good.”

If Scene Partner A messes up and calls Scene Partner B by the wrong name (the one they invented at the top of the scene), the audience will naturally notice. Scene Partner B should not stop the scene and call out Scene Partner A, nor should they make a quick joke at Scene Partner A’s expense. Instead, they want to incorporate the mistake into the scene.

Scene Partner B could respond, “Oh, I love when you call me by my old high school nickname, but I was just experimenting back then, I go by (correct name) now.”

The trick? Never make your partner look wrong.

Think about the last time somebody corrected you in public. You probably felt embarrassed – that it made you look bad.

So, how can we correct someone but still make them look good?

In dealing with clients, we can make them look good by asking questions. Especially if the boss is in front of other colleagues, asking questions helps them feel they are making decisions for themselves and taking the lead.

A good example of this happened when I was directing my feature film about applied improvisation called Act Social. I had a cinematographer with whom I had worked before. I showed him my Kickstarter funding request – which was way too low for all the things I wanted to film. He looked at it and simply asked me, “Do you think $5000 is enough for all that?”

Now, I am pretty sure he was thinking, “This guy is a lunatic, that budget is ridiculously low.” But he steeled himself and just asked a simple question which forced me to think about things realistically. He could have said, “That’s way too low, you’ll never make a feature film for that!” or any number of insulting but true statements. Instead, he chose to be diplomatic and make me feel that I was still the boss.

Emotional Point of View

Now imagine if the cinematographer had called me out on my mistake? I probably would have been emotionally upset in some way: angry, defensive, or annoyed. Any of those emotions would have affected the ensuing conversation and the working relationship.

In an improv scene, one partner initiates the scene with a basic idea. The problem with being the second actor in the scene is you are waiting to see what the initiator will do. And so, you essentially stand with a blank expression on your face waiting for direction from your scene partner.

To combat this, a great improv teacher from Chicago called Mick Napier, came up with the phrase, “Take care of yourself first.” What he meant in part was this: Even if you partner is initiating, you don’t have wait to decide what emotion you are feeling about whatever they are going to say to you. So while my partner sets up that we are in a kitchen as teammates on Iron Chef, maybe I am already deciding that I am going to be stunned by whatever he says.

If he says, “Give me that pepper mill!” I might just stare at him with my jaw agape then say, “I can’t believe you just talked to me like that!” My clear emotional choice gives him a lot to work with in the scene and will affect his response.

Likewise, with clients, we need to decide what our emotional state is before meeting with people: Are we helpful, friendly, kind, warm, generous, fun, focused, playful? What emotion will best serve the situation?

On the other hand, we need to recognize that even though “business is business” and people should “leave their personal stuff at home,” everyone is a human being with emotions and cannot turn them off.

Not only do we need to identify our emotional state before and during client meetings, we need to do our best to recognize – through body language and tone – what feelings or emotions our client is feeling.

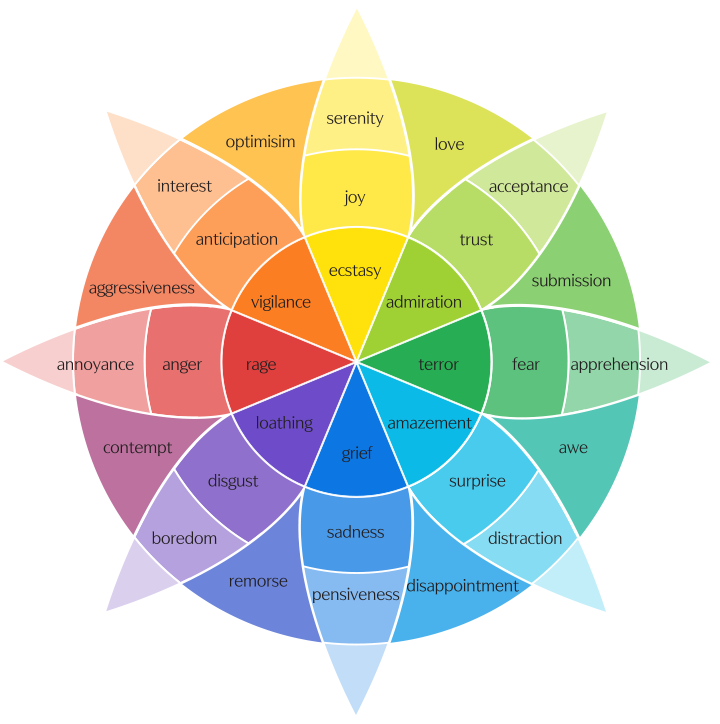

Looking at emotion maps, like Plutchik’s wheel of emotions, gives us a good idea of all the available emotions a person might be feeling at any given time. See if you can select some that might be appropriate for dealing with a particularly tough client.

If your client seems to be rushing you and you are in a helpful emotional state, you might be able to say, “Jerry, it seems like you’re in a hurry today. Is there something else urgent that you want to take care of, and we can meet later? I’m happy to be flexible with the schedule today.”

There are endless variations to people’s emotions and the better your “emotional intelligence,” the better you’ll be able to manage people. Emotions and their effects deserve our attention as freelancers, considering the havoc negative feelings can wreak on our work.

Improv is Life

We certainly can’t plan out our entire life and script how things will go. But improv gives us a principled way of living, no matter the specific situation. Try applying these techniques the next time you find yourself at an impasse with a client and who knows, maybe the whole situation will turn to Whose Line-worthy laughter!