The Homer: What Designers Can Learn from a Simpsons Classic

Closing in on its 700th episode across 32 seasons, it’s almost literally true that there’s a Simpsons reference for everything.

For the world of UX design and innovation, the best reference may be season 2’s Oh, Brother Where Art Thou?. In this classic episode, Homer meets his long-lost half brother, Herb Powell, who happens to be a wealthy Detroit auto executive faced with declining business.

In a satirical riff on competing design philosophies in the American automotive industry, Homer ends up designing Powell Motors’ next car – a monstrous contraption even by cartoon standards.

The episode perfectly encapsulates the conundrums of user-centric design, and the traps of being too reliant on experts and customers alike.

Guided By Know-It-Alls

Standing in front of a classic cartoon graph with a red line plummeting, Herb chastises his executives for being out of touch with real Americans. “You’ve forgotten your roots!”

As they pitch the name Persephone for the brand’s new car, Herb paints the difference between their ivory-tower perspective and the company’s customers, “People don’t want cars named after old Greek broads. They want names like Mustang and Cheetah – vicious animal names.”

The conflict comes to a head when Herb tries to gift a car to his long-lost brother. When Homer asks for a big car, he’s rebuffed with the statement that Americans don’t want big cars. When Homer asks for a car with a pep, he’s similarly shut down.

“Instead of listening to what people want, you’re telling them what they want,” Herb yells.

What Can We Learn from the Experts’ Failure?

It’s a claim that echoes Donald A. Norman’s Emotional Design, when he states, “Engineers and designers simultaneously know too much and too little. They know too much about the technology and too little about how other people live their lives and do their activities.”

Left to their own devices, experts grow more insular perspectives over time, even if they come from a background with a user’s perspective. Margins, efficiencies, craft, day-to-day workplace social dynamics, they all become the things we focus on actively. And they often distort our view of the user.

As designers and makers of things, we also naturally have a desire to influence and shape the world around us. It’s here where another Norman quote is an important reminder. This one from The Design of Everyday Things:

“We have to accept human behavior the way it is, not the way we would wish it to be.”

What the User Wants, the User Gets

“I want you to help me design a car. A car for all the Homer Simpsons out there.”

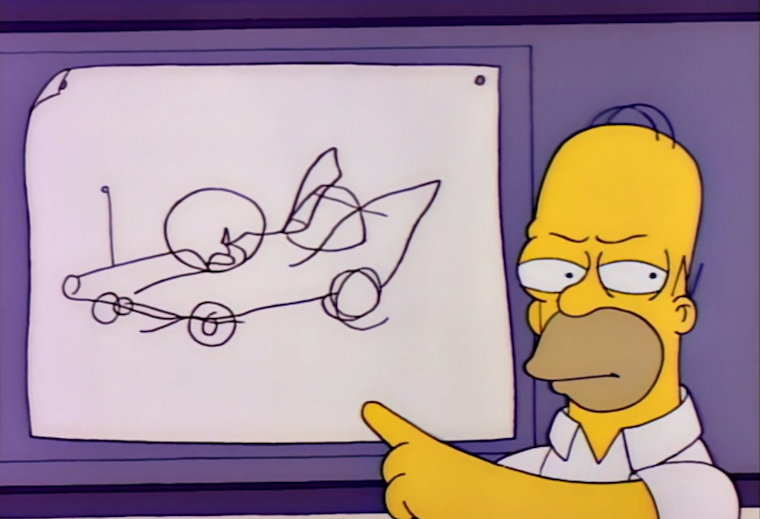

In a moment of glory for the customer-led approach, Herb turns his company’s priorities directly over to the customer. After some initial resistance from the Powell Motors engineers, Homer’s ideas become the driving force.

Homer demands multiple horns, because “you can never find a horn when you’re mad.”

“And sometimes the kids are in the backseat. They’re hollering. They’re making you nuts. There’s gotta be something you can do about that.”

It’s the kind of insight into the customer experience that companies spend millions seeking. After rejecting the suggestion of an integrated video-game console, the solution that hits the bullseye for Homer: “a separate soundproof bubble with optional restraints and muzzles.”

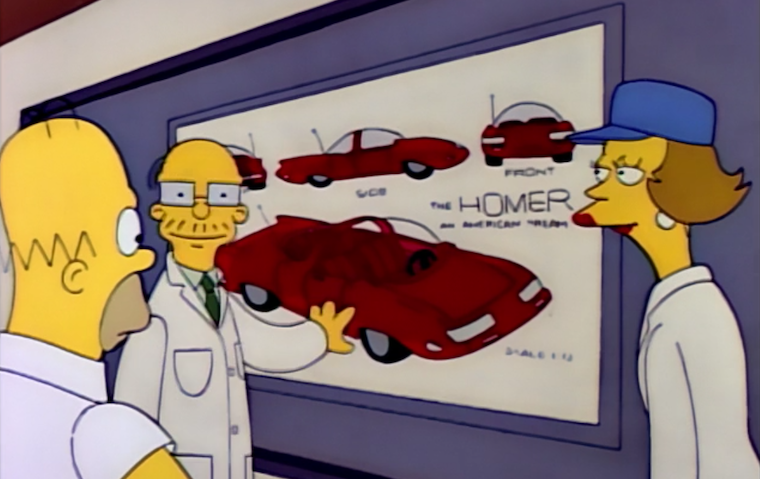

The result of all this is the iconic Homer, an $82,000 neon-green monstrosity that leaves its reveal audience speechless and bankrupts the company.

What Can We Learn from The Homer’s Failure?

In the failure of the Homer, we see the pitfalls of relying too much on users for the vision of a product or experience.

The problem? UX Myth #21: People can tell you what they want. As Zoltán Gócza demonstrates in pulling together a dozen-plus studies and examples, “you have to be aware that people make confident but false predictions about their future behavior.”

One pronounced example: In decluttering its aisles with confirmation from customers, Walmart reportedly saw same-store sales drop by $1.85 billion.

Here on the Media Temple Blog, Paul Bloag dove into the reasons why trusting users comes with express challenges and how to overcome those challenges. At the heart of his analysis:

“Here is the harsh truth, your users lie to you. They don’t always realise they are doing it, but they do lie. That means that if we take the feedback we receive from discussions with users at face value we could end up going in the wrong direction. If we want to create products and services that meet the needs of users we need to do more than just listen to what they say.”

Defining the Role of the Designer

Homer is representative of the customer Powell Motors seeks. He provides valuable, accurate feedback. But Herb’s colossal mistake lies in applying that insight without analysis or filter – without guidance.

There’s actually a point in the design process where the engineer-developed concept art based on Homer’s suggestions actually looks viable. Homer, of course, tears it up to push forward his own scribbled vision. The right balance was under the nose of Powell Motors the entire time.

While a designer needs to root themselves in the perspective of the end user, it’s ultimately their role to build a vision of the solution and to execute it.

In a blog post titled Why You Should Never Listen to Your Customers, billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban wrote, “Your customers can tell you the things that are broken and how they want to be made happy. Listen to them. Make them happy. But they won’t create the future roadmap for your product or service. That’s your job.”

The irony of this Simpsons episode is that Herb himself was the missing piece in the puzzle. He had a sense of what customers wanted. And he invested time listening to the Simpsons family and seeing life from their perspective, reflecting on its difference from his own experience. He also knew the realities of his business and the motivations of his engineers and executives.

But Herb ceded his own role in unifying these perspectives into the vision he knew would be his success.

We can’t expect customers or advisors to do our work for us. If we want to innovate, that’s our job to do.